You Don’t Need a Weatherman: Bob Dylan and the Forecast of Modern Art

“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

So goes the line from Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” and so begins a cultural forecast that resists instruments of prediction. In the opening scene of D.A. Pennebaker’s groundbreaking 1967 documentary Don’t Look Back, Dylan drops cue cards with the song’s lyrics in a London alleyway, dishevelled yet deliberate, backed by a cameo from Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. This moment—one that predates the MTV era—helped invent the visual language of the music video. It’s a moment now canonized in music video history, but what were we really watching? A singer promoting his single? Or a performance of non-performance? Don’t Look Back did more than innovate form. At a time when documentaries were largely political exposés or promotional tools with limited public shelf life, Pennebaker’s fly-on-the-wall approach offered viewers unprecedented access to a figure transforming before their eyes. It was, as one contemporary review put it, a cinematic essay in truth-telling.

But Dylan himself wasn’t interested in making sense. With the lens of Pennebaker’s 8mm film camera, the film revealed Dylan’s resistance to performance as confession, his indifference to explanation. He appeared less like a cultural narrator and more like the weather itself: changeable, mythic, elemental. Like wind, shaping what it touches without being easily traced. Dylan’s enduring relevance has less to do with any one cultural moment and more to do with his lifelong resistance to artistic stasis. In a society that increasingly values clarity, categorization, and constant visibility, Dylan represents the opposite impulse, one of elusiveness, reinvention, and a commitment to transformation over consistency. His legacy reveals that creating space for disruption easily eclipses giving direction. That is where we begin.

Leaping into the Complete Unknown

Flash forward from 1967 to 2025—James Mangold’s biopic A Complete Unknown takes on the impossible task of portraying an artist who built his career on contradiction. Anchored by Timothée Chalamet’s performance as the young Dylan, the film resists hagiography. Instead, it presents us with a flawed, hungry, and occasionally callous version of the artist as a young man, one who crashes into New York with a rucksack, a guitar, and a will to make an impact. Casting Timothée Chalamet as Dylan is a commendable strategy. Chalamet, known for portraying conflicted, emotionally layered characters, embodies a version of Dylan that resonates with a younger generation navigating its own uncertainties about identity, art, and authenticity. Indeed, the Dylan we meet isn’t polished or kind. He tramps through other people’s generosity, seduces deliberately, and borrows personas the way others might borrow coats. Yet it’s precisely this restlessness, this refusal to settle into likability or logic, that makes him compelling. In one memorable scene, he strums a guitar in his underwear, claiming to have learned chords from a cowboy named Wigglefoot. Whether his seemingly ludicrous story is true doesn’t matter. Truth, for Dylan, has always been secondary to the myth that might grow in its place.

This approach reflects Dylan’s narrative strategies in his memoir Chronicles, Volume One. Dylan rejects the role of generational prophet even as it was being imposed upon him, writing, “Whatever the counterculture was, I’d seen enough of it. I was against it. I had other things to do.” This rejection of imposed identity speaks directly to the current cultural atmosphere, in which public figures are often expected to maintain coherence across various platforms. Thus, when identity is curated across digital platforms and artists are expected to provide consistent messaging, Dylan’s early chaos feels refreshingly out of sync. Gen Z’s newfound fascination with him vis-à-vis A Complete Unknown—filtered through Chalamet’s ambivalent stammer and expressive interiority—suggests a craving for figures who don’t explain themselves. For us “Gen Zers” growing up amid algorithm-driven self-presentation and the pressure to brand one’s personality, Dylan (the rebellious artist who refuses to explain or brand himself) offers a provocative counter-model of how to resist the tidy coherence demanded by online branding and reflects a desire for ambiguity in a time of overexposure.

The Wind Blows On: Dylan’s Ongoing Cultural Weather and the Rebirth of Artistic Urgency

In his 1965 song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” Dylan delivers one of his most quoted lines today: “He not busy being born is busy dying.” The philosophical sentiment is stark, but not cynical; it is an aesthetic challenge. Perhaps the artist’s role is to undergo continual renewal, to resist finality. Dylan’s catalogue is vividly reminiscent of this process. Dylan’s early songwriting was profoundly shaped by the political turbulence of the 1960s, drawing on the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and broader currents of social unrest. For example, in his 1962 “Blowin’ in the Wind,” we hear the language of protest at its most crystalline: open-ended questions posed with the cadence of scripture. This folk anthem sounds less like a manifesto and more like a litmus test for moral attention. But by the time we arrive at his 1965 “Like a Rolling Stone,” clarity has collapsed into chaos, and Dylan has electrified his sound, leaving many fans disoriented or outraged. However, his ostentatious transition cannot be neatly categorized as a sonic evolution; it was a whimsical rupture in aesthetic expectations where he demonstrated that one could embody the spirit and ethos of folk music while employing the instrumentation traditionally associated with rock and roll. Following this break with tradition, the opening (and a personal favourite) track of his 15th studio album, Blood on the Tracks (1975), “Tangled Up in Blue,” introduces a new kind of disorientation. Instead of stemming from volume or genre, it is rooted in fragmented narrative and temporal dislocation. Time folds, refracts, and overlaps. Dylan steps into the role of literary craftsman, weaving multiple timelines into a single emotional thread. Across verses, the perspective shifts fluidly between the first and third person, destabilizing the boundary between the storyteller and the character. One moment, he’s reflecting on a shared history; the next, he’s encountering the woman anew, as if past and present were speaking through each other. Pronouns change, settings shift—from the Great North Woods to New Orleans to a topless place on Montague Street—all without temporal markers to clarify sequencing. As such, the song functions less like a diary and more like a prism: each verse refracts a different facet of the same unresolved love (surely, it is no surprise that in 2016, Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature). But if “Tangled Up in Blue” fractured narrative in service of emotional ambiguity, Dylan’s following metamorphosis fractured expectations entirely. In the 1979 “Gotta Serve Somebody,” a song from his gospel period, Dylan turns to faith as yet another act of self-reinvention. The shift from poetic ambiguity to religious conviction caught many listeners off guard. Met with skepticism and even derision, this turn was seen as a betrayal by some of his secular fans. Yet, the pivot reveals that artistic vitality necessitates the courage to alienate oneself. Dylan’s embrace of gospel was not a retreat from complexity, but rather an embrace of a new kind. As a result, what’s clear is this: art evolves not by staying comfortable, but by risking discomfort in pursuit of something truer.

Taken together, Dylan’s musical throughline teaches artists and art appreciators alike that contradiction is not failure but proof of motion. His career suggests that to remain creatively urgent, one must be willing to accept the cost of reinvention. For young and emerging artists today, this offers an equally vital lesson: growth will always entail rupture, disapproval, even reinvention that borders on self-erasure. Dylan’s influence is evident in the work of contemporary musicians who similarly resist genre and identity boundaries. Rapper Kendrick Lamar, for instance, seamlessly shifts between musical traditions and personal histories, crafting albums that feel more like cinematic experiences than conventional records. Indie singer Mitski uses sparse lyrics and shifting styles to evoke emotional states rather than linear narratives. And Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter blends genres traditionally viewed as oppositional and reclaims them under a broader, historically aware sense of cultural expression.

Forecasting Without a Map

I can’t help but wonder: what would Dylan look like today, inside our machine-driven media ecosystem? Would Spotify categorize him by mood? Would TikTok reduce him to a soundbite? Would AI try to write his next song? In an epoch when algorithms optimize cultural output for predictability, the ethos Dylan embodied becomes urgently instructive. His career was marked by an ongoing refusal to be captured, branded, or forecasted. In fact, he left behind the folk hero of the early 1960s precisely because he knew that motion is the only honest form of artistic life. And ostensibly, he resisted the very forces that now define digital culture. In such a context, the role of the artist cannot be to mimic authenticity or repackage what has already been proven to work.

Luckily, Dylan offers us a different model: one in which the artist is a provocateur rather than a producer, a seeker rather than a brand. The future of creativity may hinge on how we use technology to amplify contradiction, rather than ironing it out, turning new tools into catalysts for complexity, not shortcuts to sameness. Just as Dylan used the electric guitar not merely to amplify his sound but to fracture the folk tradition from within, artists today might use machine learning, generative algorithms, and virtual media to interrogate the very boundaries of authorship, genre, and self. What if artificial intelligence weren’t tasked with mimicking human creativity but with challenging our assumptions about it? What new forms might emerge if we stopped asking machines to sound like us and started asking them to surprise us, inviting them to introduce noise, friction, or estrangement into the signal? To imitate Dylan’s voice is easy; to carry forward his ethic of disruption is far harder. As the cultural landscape becomes increasingly saturated with synthetic forms of coherence, his legacy reminds us that real artistry lies not in the seamless, but in the jagged, the jarring, the unfinished. In that sense, Dylan does not belong to the past. He is the test we must continue to pass.

You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows. But in Dylan’s case, you might just need to stand still long enough to feel it.

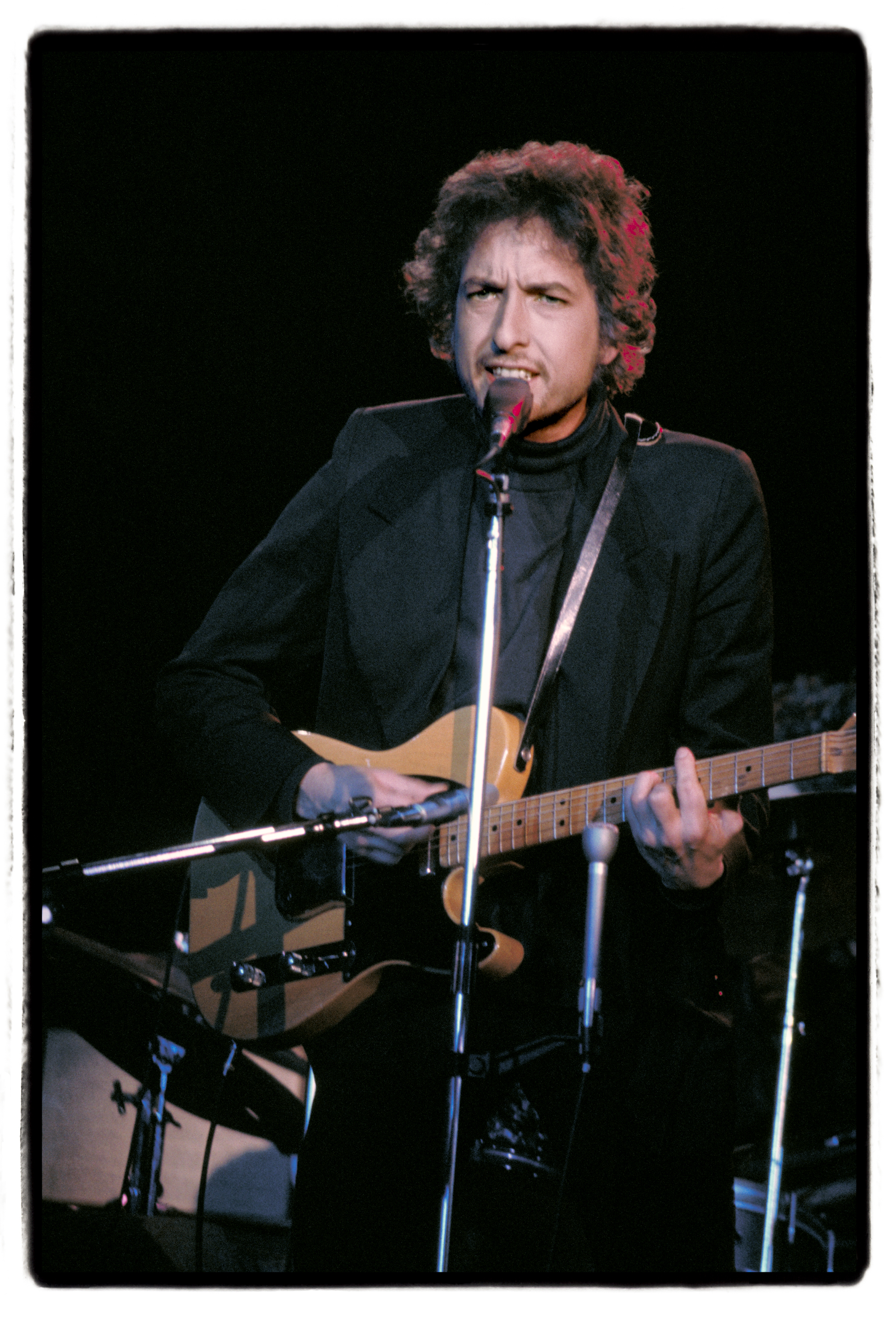

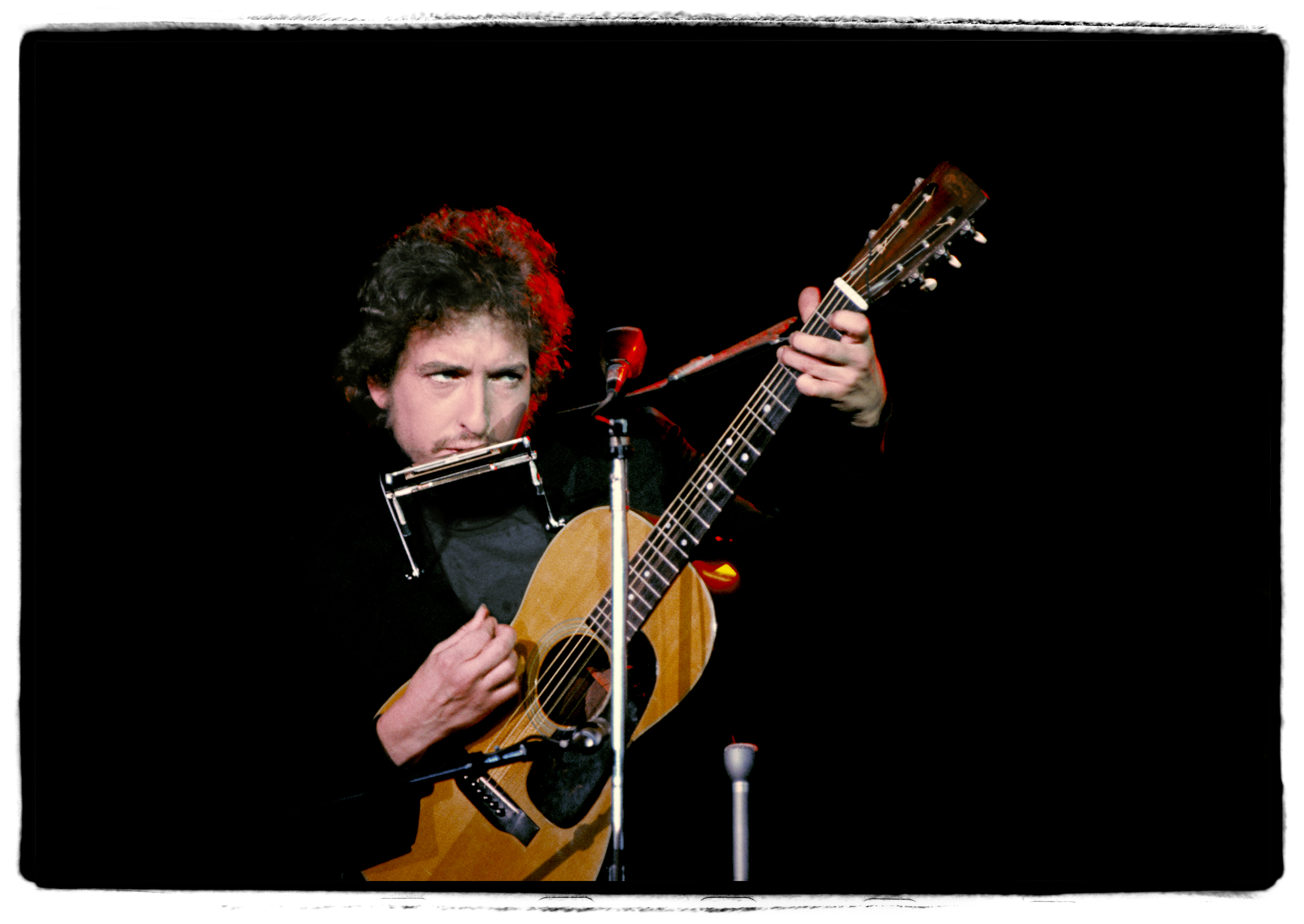

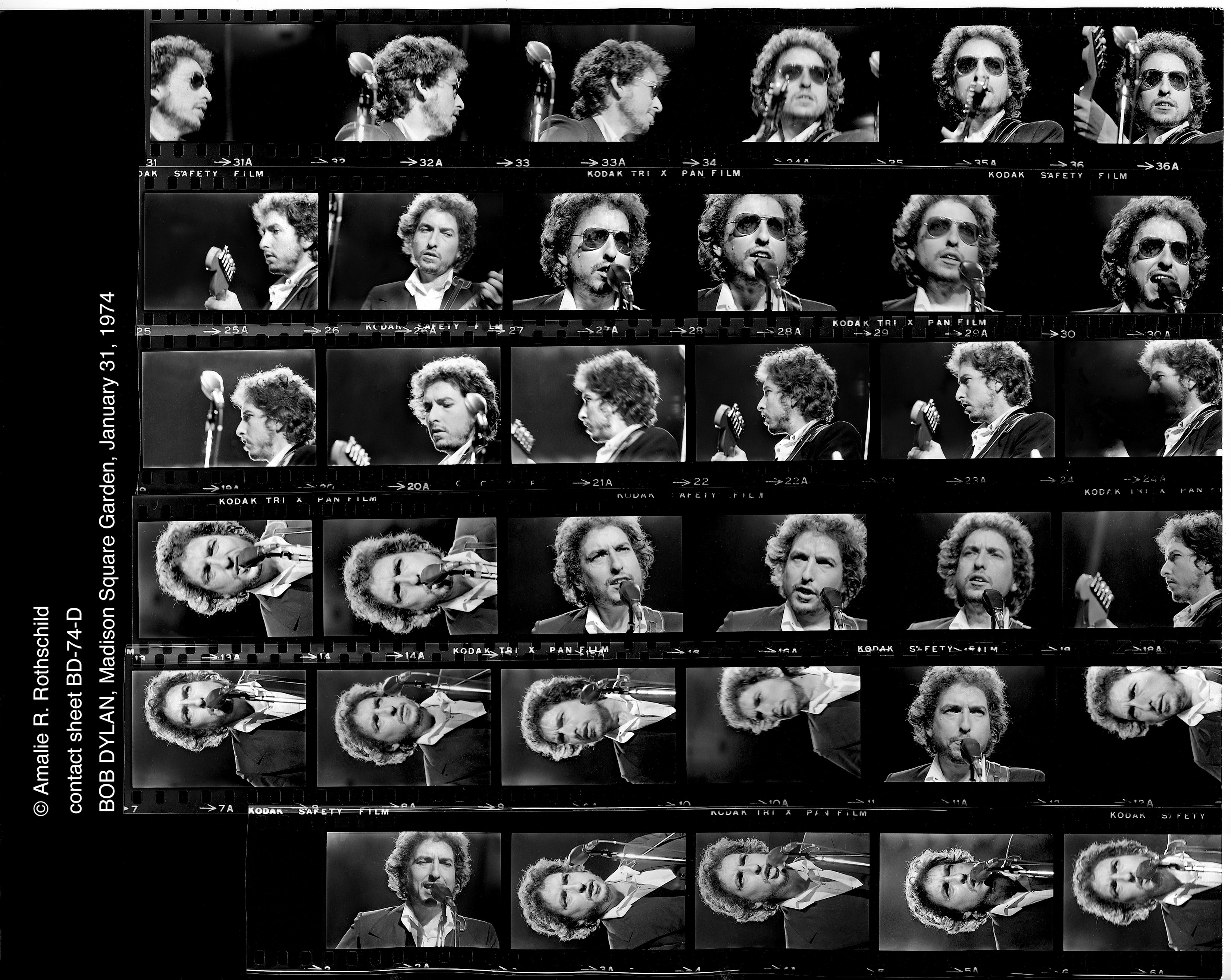

Amalie R. Rothschild is one of the four founders of the successful and progressive 54-year-old distribution cooperative New Day Films. An award-winning filmmaker and photographer she is noted for her documentaries about social issues as revealed through the lives of people in the arts. Ms. Rothschild’s keen eye has documented seminal events in history, and she is also the author of Live at the Fillmore East: A Photographic Memoir. Her films include the groundbreaking It Happens to Us made in 1971 with an all-woman crew and the first American film to argue that women should have the right to control their own bodies and end a pregnancy. Other films are Nana Mom and Me, Conversations with Willard van Dyke, Woo Who? May Wilson and Painting the Town: The Illusionistic Murals of Richard Haas.